1. Colonial Expansion & Administrative Changes

- British East India Company Influence:

By the early 1800s, Palamau and Ranchi were under indirect British control following the decline of regional powers and the expansion of Company rule after the Battle of Buxar (1764). - Zamindari System Introduction:

Traditional tribal land rights were disrupted by the Permanent Settlement (1793) and the introduction of the Zamindari system. Tribal land was handed over to non-tribal landlords (Dikus). - Revenue Pressures & Legal Changes:

The British focus on revenue extraction led to the imposition of unfamiliar legal and administrative systems, often favoring moneylenders and landlords over indigenous communities.

2. Tribal Communities & Rising Discontent

- Key Tribes:

- Kols (an umbrella term used by the British for various tribes)

- Mundas

- Oraons

- Hos

- Core Grievances:

- Loss of Land: Alienation from ancestral land due to debt, land grab by Dikus, and legal manipulation.

- Exploitation: Tribal people were often reduced to tenants, bonded laborers, or landless workers.

- Erosion of Tribal Autonomy: Displacement of traditional tribal leaders (Mankis and Mundas) by revenue agents and courts.

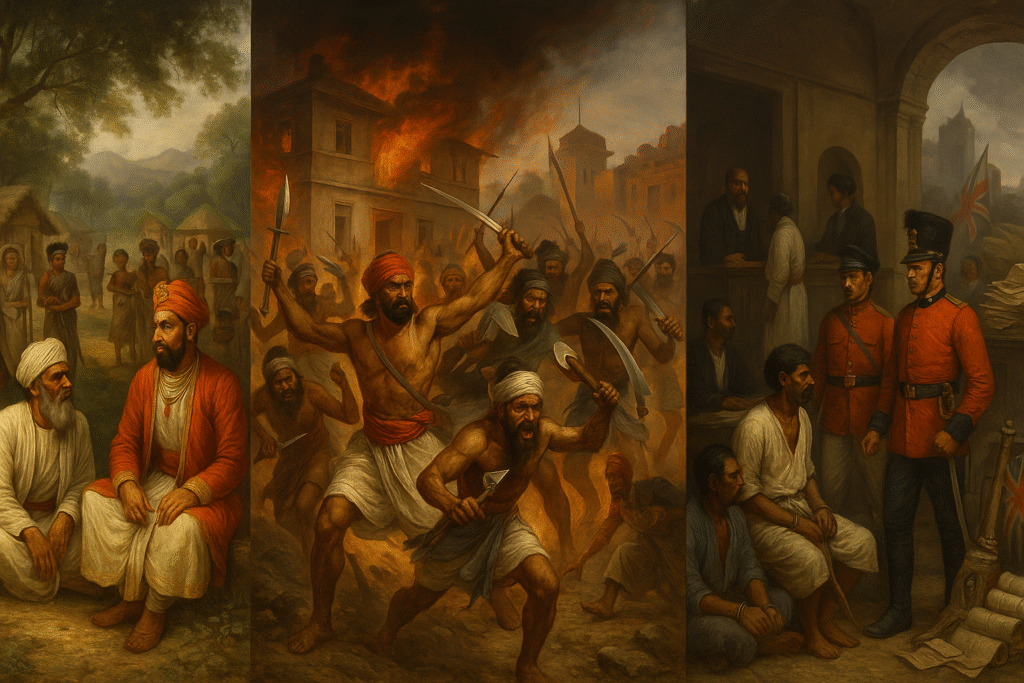

3. The Kol Insurrection (1831–1832)

- Outbreak and Spread:

Originated in Chotanagpur Plateau, particularly in Ranchi, Palamau, Singhbhum, and Hazaribagh.

Triggered by growing resentment against landlords, moneylenders, and colonial authorities. - Nature of the Uprising:

- Tribal groups launched coordinated attacks on zamindars, moneylenders, and colonial establishments.

- It was both an anti-colonial and socio-economic revolt, deeply rooted in defense of tribal autonomy and land rights.

- British Response:

The uprising was brutally crushed using military force by early 1832.

British officers underestimated the depth of tribal anger and the organizational ability of the insurgents.

4. Aftermath & Legacy

- Suppression and Control:

The rebellion was suppressed, but it forced the British to recognize the volatility of tribal regions. - Policy Changes:

The British adopted a more cautious approach in tribal areas, later formalized in the “Excluded and Partially Excluded Areas” provision of the Government of India Act (1935). - Historical Significance:

- One of the earliest large-scale tribal uprisings against British rule in India.

- Set the stage for later uprisings like the Santhal Rebellion (1855–56) and Birsa Munda’s Ulgulan (1899–1900).

📌 Core Themes and Context Before the Kol Insurrection

1. Root Causes of Unrest in Tamar and Chotanagpur

- Discontent with British authority: Many zamindars (e.g., of Itaki and Tamar) never fully acknowledged British civil or military authority.

- Terrain and geography: The hilly, forested regions provided excellent defense for local tribes and insurgents.

- Poor communication and trust: There was little governmental effort to bridge the understanding gap with the tribals; legal recourse was inaccessible, and retaliation became the norm.

- Oppressive local rulers: Chiefs like Govind Shahi were seen as oppressive, triggering resentment and violent uprisings.

2. Key Figures and Incidents

- Govind Shahi (Tamar Chief): Allegedly oppressive, his disputes with local chiefs and common people catalyzed unrest.

- Major Roughsedge: British military officer trying to suppress the rebellion, strategically cautious but ultimately forceful.

- Colvin (Magistrate of Jungle Mahals): Tasked with understanding and resolving the disturbances diplomatically, emphasizing mild and conciliatory approaches.

- Kunta Munda & Rudan: Charismatic tribal leaders of the rebellion, eventually captured but remained symbols of resistance.

3. Timeline of the Tamar Disturbances (1819–1821)

- August 1819: Outbreak begins; unrest escalates rapidly by September.

- Late 1819: British send small forces; insurgents gain ground and attack Govind Shahi’s stronghold.

- Dec 1819 – Jan 1820: Major engagements, insurgents entrenched in Purana Nagar, eventually pushed back to forest areas.

- March 1820: Rebellion is mostly suppressed; leaders like Rudan still at large.

- July 1820: Rudan arrested.

- Early 1821: Rumors of renewed uprisings led by Kunta; ultimately foiled by British vigilance.

- Mid-1821: General pacification in Tamar and Chotanagpur.

4. Extension into Chotanagpur (1821)

- Inspired by Singhbhum’s Larka Kols, unrest spreads to Chotanagpur.

- Fuelled by internal political tension (e.g., return of Radhanath Pandey).

- Suppressed again by May 1821.

🧩 Broader Historical Significance

- The Kol Insurrection of 1831 did not erupt in a vacuum—it was preceded by decades of tribal discontent, land disputes, oppressive tenures, and disregard for tribal customs.

- Tamar’s experience (1819–1821) reveals a prototype of tribal rebellion: charismatic leaders, localized grievances, strong terrain advantage, and deep-rooted mistrust of external rulers.

- The British, while attempting some conciliation, largely relied on military suppression and cooperation with compliant local rulers like Govind Shahi.

Palamau and Ranchi Before the Kol Insurrection

I. Decline of Traditional Authority

1. Nagbanshi Ruler’s Waning Influence

- Jagannath Shah Deo, the Nagbanshi ruler, was held in high esteem by subordinate chiefs and tenure-holders even in 1827.

- His authority included:

- Formal recognition of inheritance.

- Conferment of titles to subordinates.

2. British Humiliation of Native Authority

- British officers viewed the Nagbanshi’s continued authority as intolerable.

- Jagannath Shah Deo resented British policies and was aware of the exploitation of his people.

- W. Blunt (1832) wrote that the management system in Chotanagpur was “extremely unpalatable” to the Rajah.

II. Oppression of the Tribal Population

1. Economic Exploitation

- Tribals were burdened with:

- Obnoxious taxes.

- Illegal exactions from jagirdars, thikadars, and lessees.

- J. Thomason described how:

- Tribals were forced to provide unpaid labor.

- Fined for events like deaths in their own homes.

- Subject to cesses for horses, palanquins, cows, and even pan.

2. Violation of Tribal Autonomy

- The Hundeea tax imposed on homemade liquor violated domestic privacy.

- Although abolished in 1826, its negative legacy persisted.

III. Breakdown of Justice and Administration

1. Displacement and Dispossession

- Tribals were often evicted from ancestral lands.

- British courts were inaccessible and alien to tribal customs.

- Tribals were viewed as rebels rather than rightful claimants.

2. Administrative Alienation

- After 1817, local magistrates were replaced by outsiders from Bengal and Bihar.

- These officials:

- Did not understand tribal life.

- Often participated in exploitation.

3. Corruption and Illegal Exactions

- Subordinate officers demanded:

- Gonaligaree, Sulamee (customary payments).

- Opium fines, post charges, and more.

IV. Widespread Discontent and Preparations for Revolt

1. Beyond the Tribes

- Discontent was not limited to tribals.

- Even big landlords and zamindars were dissatisfied due to:

- Short-term revenue settlements.

- Legal technicalities causing estate auctions for arrears.

2. Humiliation of Elites

- British legal system was perceived as leveling:

- Even high-ranking natives were subject to criminal prosecution.

- Considered culturally humiliating by Hindus and Muslims alike.

3. Move Toward Insurrection

- The situation led to a climate ripe for revolt:

- A sense of shared suffering across communities.

- Tribals were especially motivated to reclaim autonomy.

V. Historical Context and Final Push Toward Insurrection

1. Historical Sovereignty

- Nagbanshis and Cheros had resisted Mughal dominance, retaining real control.

- Their political culture developed in relative isolation but absorbed external influences (e.g., architecture, administration).

2. Company Annexation

- By 1760s–1770s:

- British East India Company sought to annex Palamau and Ranchi due to:

- Maratha threats.

- Refuge of rebellious zamindars.

- Drip Nath Shah of Chota Nagpur submitted peacefully.

- Chitrajit Rai of Palamau resisted but was eventually subdued in 1771.

- British East India Company sought to annex Palamau and Ranchi due to:

3. Reduction of Native Power

- By 1813, the Chero dynasty was extinguished.

- In 1817, Nagbanshis were reduced to the status of zamindars.

- Tribal leaders and former allies like Jainath Singh, Sugandh Rai, and Gajraj Rai resisted British authority.

VI.Seeds of Insurrection

- The British failed to understand or address:

- Cultural values.

- Land rights.

- Administrative justice.

- Frequent revolts (1775–1830) foreshadowed the Kol Insurrection.

- The rebellion was not merely spontaneous—it was the culmination of decades of suffering, humiliation, and systemic neglect.

- The Kol Insurrection (1831–32) became an expression of collective resistance:

- By tribals.

- By former ruling families.

- By dispossessed elites.